It may be unfair to call the trio-system a failure but it is definitely unfair not to call for an end of it. PSO has become coarser and more overflowing. Its agility only makes its sound feel lack of integration. Different conductors bring different ideas and sound tonality, but overall an orchestra needs its own characteristic caliber which can only be acquired through years of systematic training under the same baton which oversees the procedure in the long term. I would defend for any accusation that puts PSO as a second grade orchestra, but it has been a while that I leave Heinz Hall on some Friday nights, untouched.

With $29.5 million donation from Richard Simmons, the fifth largest private gift ever to American orchestras, it is time for orchestra back to negotiation table with world class conductors. The list of music directors of PSO in the past is full of glories and legends: from Reiner, Steinberg to Previn and Jansons, the podium of PSO has been stamped by the footprint of the elites among the elites. It is just a pure white lie that PSO said it was exciting and brave to experiment trio-conducting system. The truth is that Jansons stepped down in such a bad time that no suitable, affordable conductor could take over the baton. But now the question is simple when funding is available: who is next?

No doubt I have no authority of answering such a question; it would be equally hard for me to answer the question of “who could be” since the list of candidates is discretely made up by a few. Therefore, I would only speak for myself and instead talk who I would like to see on the podium of Heinz Hall.

Andrew Davis

It is sad to know that Andrew Davis has decided not to lead PSO in future; therefore mostly likely he will leave his position in 2008. But I can never forget the night with Mahler’s Song of the Earth: The best concert of the year. At the end of the last movement, sounds became faded away. That is the moment that I knew something happened, something that would last one’s whole life. It was extremely beautiful but extremely sad so that words failed.

Andrew Davis knows more than others about the orchestra and his collaboration with PSO is the most successful among the three. It is true that he will leave at the end of the contract, but wouldn’t he reconsider it in future if PSO is in a solid financial situation?

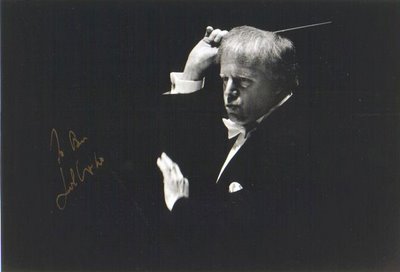

Leonard Slatkin

Slatkin belongs to those rare species among conductors. Contrary to most of the conductors moving around to find a better orchestra or a big

ger salary, He has been nurturing National Symphony Orchestra like father to son for more than a decade. At one time, he even asked to lower his salary to help overcome financial problems.

ger salary, He has been nurturing National Symphony Orchestra like father to son for more than a decade. At one time, he even asked to lower his salary to help overcome financial problems.Slatkin brought a splendid Holst’s “The Planet” last year. Even though he was called for to replace Hickox in a rush, he filled the stage with timeless space. (At one time, he re-lowered his baton at the start just to make sure everyone had been seated and ready for the music) He has the magic power to explore the sound possibility of PSO with depth and insight, and what’s more, PSO is crying for a conductor who is willing to take Heinz Hall as a home and see the growth of the orchestra.

Manfred Honeck

Only been to steel city twice, Mr. Honeck has already mesmerized Heinz Hall and conquered music critics here. When the trio-system ends, he will be 50, which is regarded as the start of the golden-time for conducting career. Only through his baton, PSO became more homogeneous, cohesive and transparent, with its string section singing like angel and horn principle gave the best solo for Tchaikovsky I’ve ever heard. What else does PSO look for other than a talented, refreshing conductor?

Only been to steel city twice, Mr. Honeck has already mesmerized Heinz Hall and conquered music critics here. When the trio-system ends, he will be 50, which is regarded as the start of the golden-time for conducting career. Only through his baton, PSO became more homogeneous, cohesive and transparent, with its string section singing like angel and horn principle gave the best solo for Tchaikovsky I’ve ever heard. What else does PSO look for other than a talented, refreshing conductor?