Although Sir Edward Elgar dedicated his violin concerto to Kreisler, it is Yuhudi Menuhin who introduced the contemporary work to the public at the age of 16. In his biography, he describes Elgar’s music as “English” as the flexibility within restraint of a weather which knows no exaggerations except in changeableness. And the response to it of a people able to distinguish infinite degrees of gray in the sky and of green in the landscape never takes either to unseemly extreme.

Half a century ago, Menuhin played the violin concerto under the baton of William Steinberg in the Syria Mosque. At that time outside English only US would welcome Elgar’s music. Today British music still never dominates concert halls but Elgar’s works have been regarded as classic.

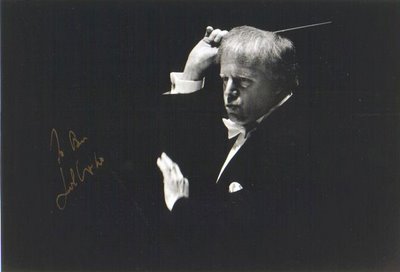

Leonard Slatkin stepped in when British conductor Richard Hickox couldn’t make his trip to Pittsburgh, accompanied by superstar Gil Shaham. It was a night of two American artists for two English composers. Surprisingly, it was a feast of sound: warm, spirited for Elgar and imaginative, spectacular for Holst.

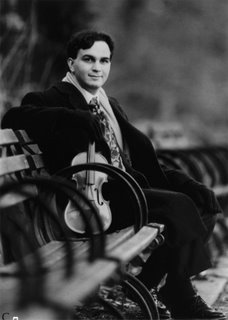

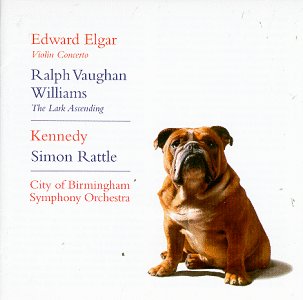

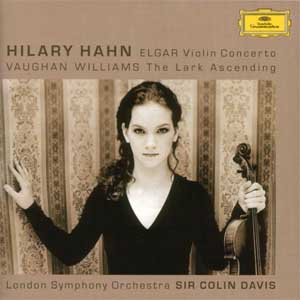

Leonard Slatkin stepped in when British conductor Richard Hickox couldn’t make his trip to Pittsburgh, accompanied by superstar Gil Shaham. It was a night of two American artists for two English composers. Surprisingly, it was a feast of sound: warm, spirited for Elgar and imaginative, spectacular for Holst.I have never quite understood the structure of Elgar’s violin concerto. It is said that Elgar always used separate sheets of manuscript paper so that he could shuffle them at will to compare the piece’s various sections. By the time of recapitulation in the third movement, I’ve usually lost my attention. Mildness is the best way to describe how Slatkin treated the work. The orchestra sound was passionate but not aggressive or vocalic. It had a feeling of wet air from the coast carried from ever-rolling surges of waves. Gil Shaham possessed an attitude of independency and objectivity, just lingering over the orchestra. His tonality was mild and romantic, but never sentimental or too-restrained. The collaboration between the violin and the orchestra seemed seamless in that orchestra was never obtrusive even in assertive section while violinist listened to the conductor attentively for every nuance in volume, phrasing and mood.

Holst’s “The Planets” has definitely been overplayed. Most people enjoyed some famous sections (Part of Jupiter has been used for lots of sports events) in the way of listening to pop music so that it has become commercial music played by an enlarged orchestra. On the other hand, “The Planets” has been undervalued or under-appreciated since seldom do people listen to it in a whole. Slatkin explored the extremity in loudness in PSO for the first movement “Mars”. He made a super crescendo from loud to deafening and the power of the orchestra could blow off the roof of Heinz Hall. After wind section showed its delicacy in Venus, Slatkin made surprising Jupiter interpretation by unique phrasing. Under his baton, it did not has a march tempo but instead carried light unevenness like a weighty wheel spinning and springing on slightly rugged road. When the singing from Women of the Mendelssohn Choir of Pittsburgh floated away in a mystery atmosphere, I suddenly realized what was missing in those dissembled music play: Although each movement is completely different in character, they all share a sense of timeless space, of boundless air. Only by listening to it as a whole can one fully enjoy the craftsmanship in Holst’s magic piece. That makes any attempt to use “The Planets” as Hi-Fi audition shallow and ridiculous.

Holst’s “The Planets” has definitely been overplayed. Most people enjoyed some famous sections (Part of Jupiter has been used for lots of sports events) in the way of listening to pop music so that it has become commercial music played by an enlarged orchestra. On the other hand, “The Planets” has been undervalued or under-appreciated since seldom do people listen to it in a whole. Slatkin explored the extremity in loudness in PSO for the first movement “Mars”. He made a super crescendo from loud to deafening and the power of the orchestra could blow off the roof of Heinz Hall. After wind section showed its delicacy in Venus, Slatkin made surprising Jupiter interpretation by unique phrasing. Under his baton, it did not has a march tempo but instead carried light unevenness like a weighty wheel spinning and springing on slightly rugged road. When the singing from Women of the Mendelssohn Choir of Pittsburgh floated away in a mystery atmosphere, I suddenly realized what was missing in those dissembled music play: Although each movement is completely different in character, they all share a sense of timeless space, of boundless air. Only by listening to it as a whole can one fully enjoy the craftsmanship in Holst’s magic piece. That makes any attempt to use “The Planets” as Hi-Fi audition shallow and ridiculous.

No comments:

Post a Comment