Two Quartets in Two Nights

Part 1 Music Dim Sum From Ying Quartet

Ying Quartet’s performance was titled “A Musical Dim Sum”, a referral not only to the dim sum food provided after the performance but also to the music pieces of the night.

The event was not originally listed on Pittsburgh Chamber Music Society season schedule and didn’t attract too many gray-haired subscribers. In fact, had not the real dim sum been provided, the musical dim sum may not have found audience to serve. Once the performance was over, the food line took over the whole lobby and everyone seemed to be talking about gourmet immediately. Because of the poor publicity, most of the tickets were given away to the students, especially Chinese students, who eventually enjoyed both forms of dim sum in the end.

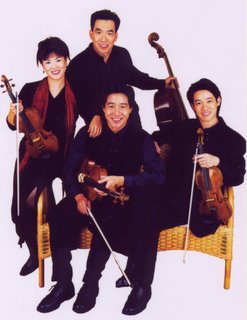

Ying Quartet is formed by four siblings in a family. The three brothers and a sister were born and raised in Chicago and now teaching at Eastman (University of Rochester). David Ying, the cellist, is the eldest. When talking in the stage, he constantly waved his body as if he were performing. But once playing the cello he is motionless with his eyes half shut and his eyebrows frowning intensely. Phillip, the violist, is easy-going and took over the job of explaining music program to the audience. He talked softly, with disarming smiles, “Most of the quartets will only feature two or three works for one night, like Mozart or Beethoven since each of the work is about half an hour. But tonight we’re going to give a music dim sum, which in Chinese, means ‘Zao Cha’. Instead of listening to only a few big works, we are going to taste a little bit of everything and enjoy the treat of a diverse sampling of music from our own culture heritage. If you look at your program, I am sorry, I should say MENU here (LAUGH)…” His first introduction eased the audience and more importantly set the tone of the night: It was a night of small bite, a night of something new or even bizarre. When people try new food, they tend to focus on food itself: color, smell, taste or even the recipe, and who cook it becomes unimportant. Their goal of the night was to cross the boundaries of the traditional classics and lead the audience into new forms of music without showing off themselves.

The only female member, Janet didn’t talk at all during the event. Her calm white complexion stood out among men in black but belied her ardor in music and the fact that she is fascinated by martial art. Tim, the first violin is passionate when playing. His big dark scar under his left chin shows his years’ training. Even though all three brothers wore traditional Chinese jackets in black, Tim, with his jacket open and semi-long hair, looked more rebellious than the others.

The Ying siblings began their career as an ensemble in 1992 in the farm town of Jesup, Iowa, a town of population of 2000. When I asked Phillip why they chose such a small town to begin their career, he said that was their first job, sponsored by Chamber Music America Rural Residency Program. Through years, they have given performance for audience of six to 600. In 2005, their collaboration with Turtle Island won Grammy Award of Best Classical Crossover Album. I haven’t had the chance to listen to that album, but Phillip told me that it was a combination of Classical and Jazz and they like to try them both

It was surprising that the event was not held in conventional Carnegie Music Hall, but instead in KAPA, a local art school. Such a small space increased the intimacy and communication between the players and the audience. Every one sat close enough to see how the members felt the music in a state of perceiving and engaging other than mere listening. The program featured works by Chinese composers who reside in US in the first half and ended with Debussy’s quartet in the second half. Except Tan Dun, I am not familiar with any other Chinese composers. But the introduction of each piece by the members before playing made listening experience much easier.

The first piece, Chen Yi’s “Shuo” brought Chinese folk music into quartet format. “Shuo” in Chinese means initiate and represents the first day of every month in the lunar calendar. Chinese music features a lot of percussion and non-harmonic elements, which is unique and innovative in terms of string quartet format. There are two elements in the piece. One mimics mountain songs by three instruments weaving into different layers while the other (mostly the first violin or the viola) singing above like a song penetrating the sky above layers of delicate mountains. Another depicts the fierce dancing in southwest China. Suddenly all members patted on the instrument. The primitive sound was short and restrained, with a sense of ardent dance rhythm, followed by boisterous theme with continuous downbeat. My friend almost burst out laughing when he heard the playful slapping sound, but in the end it was the mountain song with pentatonic melody lines that connected the audience (mostly Chinese) with the music.

It was sad that people remember Tan Dun only by the film score of “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”. His “Eight Colors for String Quartets” was written in 1987 when he went to New York. The so-called colors are abstract in title but rich in form and tonality. In fact, each short piece is not named after a color but by different titles. Ying Quartets chose three of them: “Drum and Gong”, “Cloudiness” and “Red Sona”. Tan Dun’s innovation shows its greatness with respect to dynamic timbres. I heard that he even invented his own instrument to make some special sound for the music. In this piece, the audience can feel the combination of Chinese Culture and western atonality with dramatic forms and structures. “Drum and Gong” shows the elements of Peking Opera which is one of the key music elements in many of Tan Dun’s works. In fact, had not a local Peking opera troupe been drowned in Cultural Revolution period, Tan Dun, as one of the few string players in the whole Hunan Province, could not have had the chance to be liberated from his agricultural life. The unique melody in Peking Opera, which can be easily identified by most of the Chinese, expresses a touch of western atonality. Like traditional Peking Opera, the quartet is loud and “noisy”, like a rough painting by the fighting instruments. The second piece “Cloudiness” which is hinted by varied intensity of notes from time to time goes to another extremity with the long whisper and sudden plummeted melody lines. David said that’s his favorite piece, which also became mine too. The cello first felt weightless, floating in the air, and then suddenly dropped to the bottom with a sharp brake. It was a piece full of space, indicating the essential “emptiness” principle of Buddhism.

Zhou Long’s “Song of Ch’in” is a piece constructed with immense Chinese cultural backbone. It is based on Li Zong-yuan’s poem “Old Fisherman”.

The Old fisherman moors at sun, and the man is gone;

Only the song reverberates in the green of the hills and waters.

Look back, the horizon seems to fall into the stream;

And clouds float aimlessly over the cliffs.

渔翁

柳宗元

渔 翁 夜 傍 西 岩 宿,

晓 汲 清 湘 燃 楚 竹。

烟 销 日 出 不 见 人,

欸 乃 一 声 山 水 绿。

回 看 天 际 下 中 流,

岩 上 无 心 云 相 逐。

In Chinese aesthetic concepts, less is more. The main theme of “Song of Ch’in” is quiet and sparse. Ch’in, although with seven long string, is a plucked instrument. Actually none of the traditional Chinese instruments use the same mechanism as string instruments in western music. The timbre changes because of the lack of constant vibration on the string. Ch’in, in particular, makes every note a decrescendo. Ying Quartet tackled this issue by control of contrast and vibrato. Seldom can you hear some gigantic chord by four members here, but each individual played harmonically in terms of pastoral atmosphere.

Chen Yi’s “The Talking Fiddle” was the last piece in the first half. Although it is a commissioned work for Ying Quartet, Chen Yi actually started the composing from a dumpling party. In one of Kansas City Chinese New Year party, Chen Yi heard people playing Erhu to imitate human’s voice. In particular, “Happy New Year” (Xin Nian Hao) was so vividly performed that the greeting won lots of laugh. Inspired by Erhu’s expressiveness, Chen Yi decided to write a string quartet with “Happy New Year” as the music germinal idea.

In the quartet, viola declares the greeting of “Xin Nian Hao”. When the first time the theme appeared, almost all Chinese smiled for the funny pronunciation from Phillip’s western instrument, and immediately the audience took the task of recognizing it in any metamorphic form.

It was such a great experience to be able to perceive the transformation of the theme because of my ethnic identity. Since the music cell is extremely short, the theme doesn’t possess any definite form and is transformed bravely into different emotional feelings. It is sensed as greeting at first; later on as different instruments takes a success of the theme, it becomes poignant or even ferocious sometimes. The incompleteness of the three-word-theme makes the variations as wild as possible; but the essential nature is well kept and each recapitalization grabs the attention and gratitude of being apprehended.

The key to the theme phrase is actually the last expressive word “Hao” or “Happy” in English. Hao takes the third tone in Chinese pronunciation and down beat in music. It is a drawling tone falling then rising represented by the shape of “v”. The turn-around point resembles a halfway stop sign followed by a humorous elongated rising note.

As the title indicated, the music is a talking fiddle with respect to rhythm and color, only occasionally hinted by the theme. Polyrhythm is used to confuse the communication between instruments so that at times the music sounds like four persons chatting in their own paces without listening to each other. The traditional Chinese instrument techniques such as bowing, plucking, blowing and percussion are all used to add rich color. The result is quite an intriguing piece that even the members expressed a sense of satisfaction in the performance.

Debussy’s Quartet in G minor was written in the same period as his “L’Apres-midi d’un faune”. Phillip told me that he felt that there is a strong connection between Debussy and Chinese music. “They are both so colorful, so rich.” What amazed me is that Debussy’s fond of pentatonic music creates something totally different from Chinese music in the atmosphere. It is languid and free of form, clustered as for notes but remains a sense of flow as if it is irresistibly going to develop in the way it is written no matter how refreshing, how sparkling some fragment could be.

Ying Quartet didn’t give a much different interpretation, although they tended to augment climax while subdue leisure material. It could be an effect of an aftermath from the intense Chinese music in the first half.

In most quartets, the first violin is the soul. Although the tempo may be decided by four members, the first violin has the most chances to express himself or sometimes show off. However, in Ying Quartet, it was the viola that popped out and made the most impression. Possibly it was because of the quality of the instrument; possibly it was the effect of the selected program (or menu). The viola, with its unique sound, mostly lead the program in the first half, in particularly in Chen Yi’s “The Talking Fiddle”, but the quartet was finally balanced in the second half for Debussy.

1 comment:

Chinese indie music fans share their favorite songs in www.Hoyard.com,you can go there if you are skilled chinese.

Post a Comment